Abstract

Parental mortality data from the Child Maintenance Service (CMS), the Department of Work & Pensions (DWP), and the Office for National Statistics (ONS), show that parents who are in arrears with the CMS have a mortality rate 14.28 times higher than the national mortality rate. Arrears is the financial and legal term that refers to the status of payments in relation to their due dates[1] i.e. applies to an overdue payment, and any non-compliance fines that may be levied. This subgroup forms 65.1% of the deaths of paying parents, despite being only 12.3% of that population. 93.1% of the deaths that exceed the national average mortality rate (here on referred to as excess / unexplained deaths) in the paying parent population were in arrears in the month prior to their death. The harsh treatment of these parents by the CMS in the form of methods used to enforce payment can reasonably be considered a contributing factor to the inordinately higher mortality rate of this subgroup. Despite the extensive historical protesting against the CMS and the progressive government investment into mental health support, there is an absence of investigation into the contribution of the CMS to parent death. This oversight can be considered, as a minimum, grossly negligent due to the substantially high mortality rate of paying parents in arrears, and requires urgent investigation.

Parental mortality data was provided by the CMS through several Freedom of Information Requests (FoI)[2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7]. The data covered a period of 34 months from September 2017 to June 2020. The mortality data was separated into subgroups based on the payment status of the parent at the time of their death. The mortality rates of each sub-group were compared with the expected rate for the general population and for the average age, to assess whether there was a difference between groups.

Of 1,013 annual excess deaths within the paying parent population, 93.1%, were in arrears at the time of their death. This gives the ‘in arrears’ sub group a mortality rate which is 14.28 times greater, and the ‘without arrears’ subgroup a mortality rate 1.15 times greater, than the expected rate of mortality when compared with the general population age range 30-50. This large difference in mortality rate between the two groups indicates a strong association between being in arrears and parent death. That correlation is strengthened significantly by the reduction in paying parent deaths in 2020 compared to 2019 which mirrors the reduction in CMS enforcement activity in 2020 due to Covid-19 restrictions.

According to the Samaritans, three of the highest-ranking risk factors for suicide, particularly in males, are present in most if not all CMS cases from the outset and often over the long term; 1. Relationship breakdown, 2. Separation from children and 3. Deprivation[70]. We investigate the extent to which vulnerability of paying parents is a consideration for CMS when carrying out their enforcement practices.

Our findings exemplify a link between the harsh consequences of arrears and unexplained parent death; which can reasonably be attributed to increased levels of suicide and/or other consequences of financial distress and poverty as a result of the harsh treatment by the CMS (such as homelessness and rough sleeping). Not only is this a significant economic issue but an indisputable humanitarian crisis that requires emergency attention and remedial intervention.

Introduction

It is widely recognised that both parents should, as a minimum, have financial responsibility to support their own children. When one parent is absent, sole responsibility falls on the remaining parent, which often causes financial difficulty for the resident parent and risks the child’s needs not being met. Historically, this has led to a heavy financial burden on the state, as the resident parent and child may consequently rely on state benefits. In an attempt to alleviate the economic burden on the state and ensure children are financially supported, the Child Support Act 1991 passed to make it a legal requirement that both parents contribute financially for the child's basic needs[9]; launching what would become the Child Maintenance Service (CMS) to enforce this.

The CMS is a governmental agency which oversees the financial support provided to the children of absent or Non-Resident Parents (NRP) when a Resident Parent (RP) makes an application for them to do so. This agency was established in 2012 when its predecessor, the Child Support Agency (CSA), was abolished by the government due to their failure to implement the Child Support Act 1991, which had left tens of thousands of parents paying more money than required[10], including an acknowledgement that up to 86% of the maintenance orders had been miscalculated[11]. The aim of both the previous, and the current agency, has been to provide a means to calculate and register a maintenance arrangement between separated parents, and mandate the consequences if the arrangement is not adhered to.

When a paying parent fails to meet the full payment requirement of the maintenance arrangement, they are defined as having arrears, which, if not swiftly resolved, results in being moved from a Direct Pay system to a Collect & Pay system. This gives the CMS wide reaching powers in order to enforce payment, which include:

● collecting directly from the NRP's bank account without their consent or providing notice

● deduction from a paying parents’ earnings via their employer

● suspension of driving licenses & passports

● orders for sale of assets

● and even criminal prosecution which can result in custodial sentencing

The financial consequences of inability or refusal to pay include a 20% increase of arrears already owed, a 20% increase to future ongoing payments by the NRP, and a 4% deduction from the money passed on to the Resident Parent (RP), all to be retained by the CMS.[12] This is only removed if/when the RP agrees or the CMS deem that the individual can be trusted to continue payment, decided at their discretion[13]. This is stated in the CMS briefing paper to the commons (2021) as “Those required to pay through the Collect and Pay system because they have been deemed “unlikely to pay” must demonstrate, for at least six months, that they can pay in time and in full before the CMS considers returning a case to Direct Pay.”[14]. It is understandable how repercussions such as these, especially when legislated or implemented incorrectly, can reduce the quality of life of the NRP, far beyond what is justified or sustainable. This could be a contributing factor to the large difference in mortality rate between paying parents in arrears and the general population.

Whilst an agency of this kind is necessary to ensure financial support for a child’s everyday living costs is provided by both parents, the maintenance calculations made by the CMS may not provide the NRP with sufficient money to support a basic standard of living. On top of this, the manner in which paying parents are treated by the CMS when they are unable to pay, and the extreme consequences of such treatment, suggests that the current mechanisms by which the agency works, may be causing more harm than they do good.[10]

Since its introduction, there have been continuous complaints to the CMS (and its predecessor) of maintenance miscalculations resulting in excessive claims and arrears followed by severe enforcement practices in order to collect the inflated or even manufactured arrears. Many protestors have claimed that, due to arrears inflation and enforcement procedures, CMS policies and practices result in higher levels of parent poverty. Sir Ian Duncan Smith stated, in his briefing paper to parliament from the Centre for Social Justice, that whilst the situation for receiving parents has improved, there is a reduction in the paying parent’s ability to “earn more money to support their children and escape poverty” due to the reduction in work incentive of the receiving parent[15].

It is commonly understood that poverty is a causative factor in increased physical and mental illnesses as well as suicidal ideation, as demonstrated and addressed by numerous researchers. Melzer et al (2010) stated that those in debt are “twice as likely to think about suicide” [16] and Perry and Craig (2015) address the higher mortality rate for homeless individuals with the average life expectancy of homeless people being 47 years compared to 77 years in the general population[17]. This elucidates to a potential involvement of the CMS in excess parent deaths due to their role in paying parent financial difficulty. Involvement of such has been consistently denied by the CMS and the government ministers responsible, including within FoI disclosure, where it is stated that “Although date of death is held, the cause of death is not, therefore no causal effect or link between a CMS case in arrears and mortality can be assumed from any information provided”.[3]. The correlation between the CMS, parental debt and debt/poverty related deaths places an institutional responsibility upon CMS and government to have carried out adequate research and risk analysis as to the impact of miscalculations, heavy handed enforcement and the absence of a minimum amount the paying parent is left with to meet their own basic living costs.

This report aims to identify the difference in mortality rate between paying parents in arrears, paying parents not in arrears and the general population. This is required to assess whether the enforcement practices employed by CMS can be reasonably stated to be a contributing factor in excess parent deaths, based on their in-house data. It also aims to model the financial effect that child maintenance payments have on the average paying parent in an attempt to find a cause behind higher parent poverty, as well as estimate the government increased taxation yield as possible motive / reason behind this ongoing oversight. The reduction in enforcement activity by the CMS during the Covid-19 pandemic has presented an additional opportunity to compare levels of parent death in the prior year to levels during the pandemic, in order to determine whether there is a clear link between enforcement activities and the level of paying parent mortality. The potential implications of these findings would include opening an investigation into the connection between CMS practices and the high mortality rate of parents with arrears in order to confirm or deny a relationship of causality. Establishment of a causal link between CMS and increased mortality could lead to an Independent Public Inquiry into the CMS practices, reformation of the agency and potentially senior management and ministerial culpability due to their influence in the exceedingly high mortality rate of paying parents in arrears.

Materials and Methods

Collection of data

A total of 7 Freedom of Information (FoI) requests were made to the CMS, two of these were by 3rd parties, Abbey Long[2] and M. Peberdy[8], 5 others were submitted personally[3] [4] [5] [6] [7]. The initial 3rd party FoI led to the production of a prior version of this paper[18] which will here on be referred to as ‘Report 1’. The findings of Report 1 identified a high level of excess mortality within the paying parent population as a whole; it was this finding that prompted the 2nd, 3rd and 4th FoI requests, in order to obtain insight into the proportions of the total deaths that are attributed to parents in arrears and parents not in arrears, and to investigate the financial effects of being under CMS oversight to the paying parent.

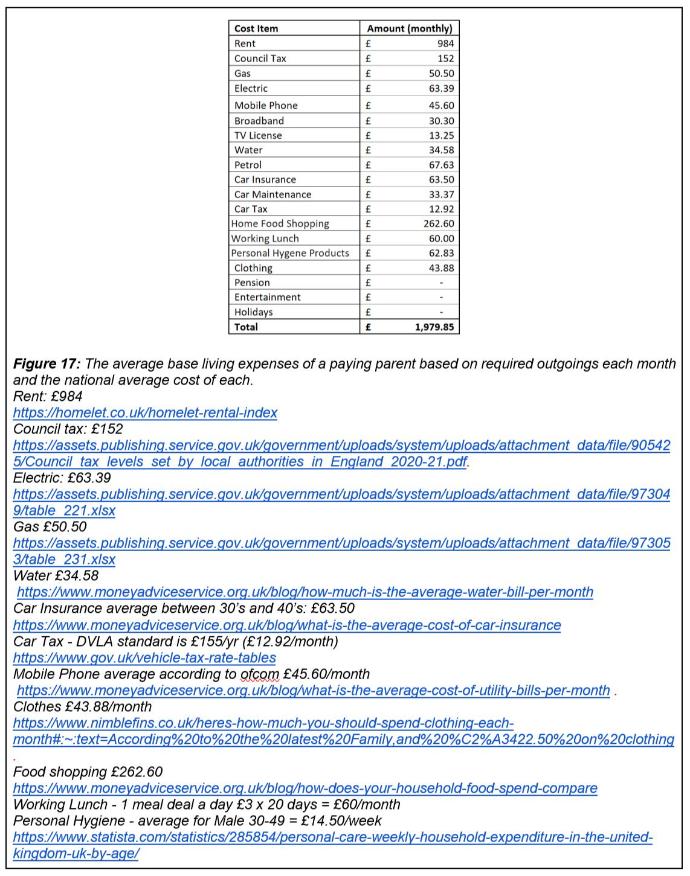

Data was also obtained from the quarterly reporting published by CMS which is accessible on the Department of Work & Pensions (DWP) website[19], including; Service User Make-up (by Gender & Resident (Receiving) Parent (RP) vs Non-Resident (Paying) Parent (NRP)), types of maintenance collection methods and their prevalence, the amounts of maintenance collected, the CMS overall population growth over time, and the level of maintenance payment compliance. In addition, the DWP data interrogation tool, Stat Xplore[20] was utilised to drill down further into CMS paying parent population characteristics. These resources were utilised to carry out basic mathematical calculations for comparing the parent mortality rates provided in the FoI’s by the CMS to the national mortality rates published annually by the Office for National Statistics (ONS). The CMS quarterly reporting also contains data to allow the average number of children per parent and level of contact that NRP’s have with their children to be calculated. In order to investigate the financial effect of being under CMS oversight, further data was obtained on the national average living expenses (see Fig 17 on page 25 for individual item citations), the taxation rates at each salary banding using The Salary Calculator[21], and the amount of maintenance to be paid at each salary band using the CMS child maintenance calculator[22].

Report 1 identified excess / unexplained deaths (deaths that are above the levels found in the ONS nationwide mortality statistics) in the CMS paying parent population of 447 per year and no excess deaths in the receiving parent population. Those findings led to the application for a further FoI, requesting the CMS to provide the following data for the 33-month period between January 2017 - September 2019 (the same dates as provided in the initial FoI).

FoI requested for:

- The total number of all-cause parental deaths from within the paying parent population of CMS.

- The total number of deaths where the deceased were in arrears, at the time that their death was recorded.

- The total amount of money owed to the CMS, due to arrears, following parent death during the time period.

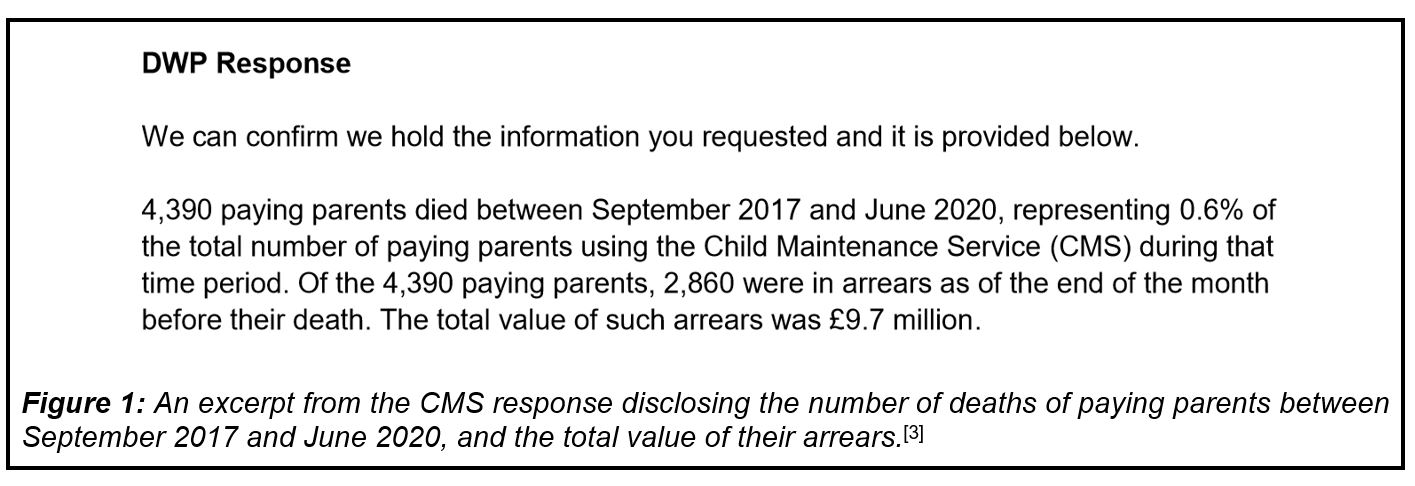

The CMS response[3] which arrived on 26th November 2020, disclosed the requested data for the later period between September 2017 to June 2020 (an increase in the period from 33 months to 34 months). Figure 1 presents the part of the document that is relevant to this paper.

|

|

The 4th FoI[5] detailed the sexes of the paying parents with arrears who had died between Sept 2017 and June 2020. This disclosure allowed us to assess the variation in death rate and excess/unexplained death rate according to whether the paying parent was female or male. This FoI also provided the total number of paying parents recorded as having arrears, however this information was not noticed until an estimate had been used in its place. Calculations using the estimate are shown in this paper, however subsequent to noticing the substantial difference in number (estimated 53,700 parents vs CMS claim ranging from a low of 241,450 to a high of 317,920 parents with arrears), it was clear that this discrepancy would materially change the outcome of the paper unless there were clearly identifiable subgroup characteristics around which higher rates of parent death were evidenced to have concentrated. Consequently, further FoI requests were submitted, largely due to the claim of much higher levels of parents being in arrears by the CMS which appeared to contradict figures contained in their own quarterly reporting.

The 5th FoI[6] resulted in a refusal on the grounds of time and cost, but contained the following explanation as to the discrepancy between the claimed high level of parents with arrears and the quarterly reporting.

“The information provided in FOI 2020/66419 and FOI2021/00527/01288 cannot be directly compared with compliance measures included in the Child Maintenance Service (CMS) quarterly statistics. The compliance measures provided in the quarterly statistics deal with the amount of maintenance actually paid by Paying Parents who were due to pay ongoing maintenance via the Collect & Pay service during each calendar quarter. For example, the latest statistics show that in the quarter ending December 2020, 72% of those due to pay via Collect & Pay actually contributed some maintenance during that quarter (but not necessarily all that was due). In contrast, the figures provided in our responses include all paying parents with any amount of outstanding unpaid maintenance, however small, regardless of when payments were missed, and regardless of whether they were liable for ongoing maintenance at the point of reporting. These two metrics are fundamentally different and cannot be directly compared.

Furthermore, in your FoI request of 31 October 2020 (FOI2020/66419), the response to which was used as a basis for FOI2021/00527 and FOI2021/01288, you specified that we include ‘Arrears Only’ cases that were carried over from the Child Support Agency (CSA). As we have noted in all relevant correspondence, such cases are not included in regularly published CMS statistics. By definition, all of these cases involve arrears. Information on the number of such cases is published in National Data Table 3 of the CSA quarterly summary of statistics, published January 2021.”

Responding to the CMS invitation to submit a revised request in order to fall within the time/cost limit, a 6th FoI was submitted asking the following questions:

1. Referring to FOI2021/00527/01288, where the data table 1 provides a monthly count of parental deaths where there are arrears in the month prior to death, split between male/female/other, please subdivide this table into two tables. The first table should be parents who had an ongoing liability to pay, the other table should be parents with no ongoing liability to pay.

2. Please carry this same data table forward to bring it up to date with the latest available records.

After a month-long delay, which meant that completion of this paper also therefore had to be delayed, the information requested was disclosed in full and facilitates much greater accuracy in calculations.

Calculations

- Percentage of the total deaths of paying parents in arrears vs not in arrears

The further disclosure from CMS allowed initial calculations to be adjusted and updated for more accurate statistics. CMS shifted forward the date range for data they disclosed from January 2017 - September 2019, to September 2017 - June 2020 (the former range is 33 months and the latter is 34 months in total). Of the 4,390 paying parents who died, 2,860 were in arrears as of the end of the month before their death, this means that 65.15% of the total deaths of paying parents were in arrears.

- Number of paying parents that were in arrears vs number of paying parents not in arrears

The CMS does not publish data as to how many cases are in arrears, as a result there has been some confusion with regards to the size of the population against which to calculate the rate of mortality. This figure has been requested as an average during the stated time frame. Whilst waiting for CMS to confirm the number of parents recorded as being in arrears, calculations were based upon following assumptions, using CMS data up to and including March 2020.[23]

It was assumed that:

● Parents paying by Direct Pay (private arrangement between parents) are not recorded as being in arrears because CMS do not monitor those payments – this population (at March 2020) accounts for 285,500 parents who would not be recorded as being in arrears.

● Parents paying by Collect & Pay (enforced payment by CMS taken straight from the paying parents bank account or as a deduction from earnings at source) amount to 148,200 parents, of which 48,000 are recorded as having not paid or not paid in full, and therefore being in arrears.

● In March 2020 a further 9,000 cases were leaving Direct Pay and going into Collect & Pay. 3,300 cases were moving in the opposite direction (presumably no longer in arrears). This would balance to a further 5,700 in arrears.

Subsequent to making the above calculations, the CMS stated that the total number of paying parents recorded as being in arrears ranged from a low of 241,450 to a high of 317,920 over the same period. The objective has always been to find the relevant sub group of the population where the death rate is out of line with national averages and disproportionate to the rest of the paying parent population, in order to identify which subset of parents are at greatest risk of premature death. The 6th FoI[7] provided the necessary data to determine much more tightly the common characteristics of a subgroup of paying parents within which the problem lies and calculate to what extent the problem is present.

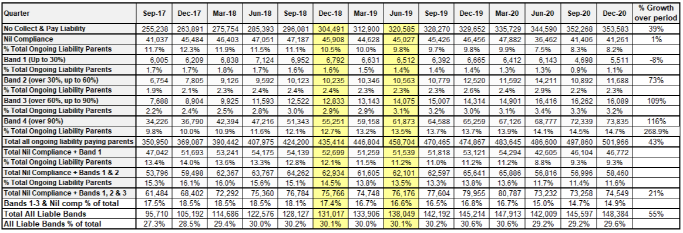

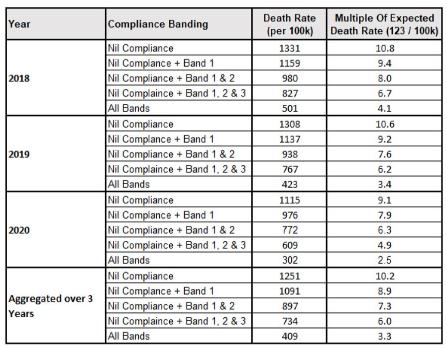

The 6th FoI included 2 tables, the first table related to parents in arrears who also had an ongoing liability to pay. The second table related to those parents with arrears but no ongoing liability to pay. In both cases the CMS did not provide a figure for the total population size of both these sub groups of paying parents, but this has since been requested. In the meantime, it has been possible to calculate this using the DWP data interrogation tool Stat Xplore[20], from which the table of data in figure 2 below was exported and some supplementary calculations were made.

|

Figure 2: Data extracted from Stat Xplore[20] with supplementary calculations added |

It is the view of the authors that the majority of the parental deaths are occurring in the lowest bands of Collect & Pay compliance. For the sake of completeness, however, calculations will be made and placed in a table showing deaths to arise only in the Nil Compliance group, then in the Nil Compliance plus Band 1 groups combined, then adding each band in turn until all bands are added together to comprise a group of all Collect & Pay cases with ongoing liability. To add weight to the belief that most parental deaths will be occurring within the lowest 2 bands (Nil Compliance & Band 1 - up to 30% compliance) it is notable (see table Fig.2 above) that the volume of parents recorded as having Nil Compliance has stayed almost static since September 2017 (just 1% growth) and the volume of parents recorded as up to 30% compliance has shrunk by 8% over the same time period, whereas all the other bands have seen substantial growth in parent numbers (Band 2 - 73% growth, Band 3 - 109% growth and Band 4 - 116% growth). Therefore these 2 lowest compliance groups are ‘bucking the trend’ of overall CMS paying parent population growth, which collectively has increased by 43% overall and the Collect & Pay portion of that population has grown by 55% since September 2017. The groups where the greatest financial pressure is present being likely to experience the highest death rate, would naturally lead to a slower rate of growth (or even reversal) in those subgroups than we are seeing in the other groups, due to the deaths of a disproportionate percentage of those parents, and financial distress is heavily linked to suicide causation.

A further FoI request has been made[24] to subdivide the parental mortality data provided, by the compliance band they are attributed to at the time of their death. The columns shaded yellow in the table in Fig 2 are due to CMS data in those quarters not being distributed into the correct bands, therefore manual calculations were made taking a midpoint number between the quarter prior and the quarter after these shaded quarters.

- Sex of paying parents who died

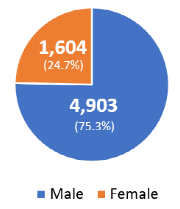

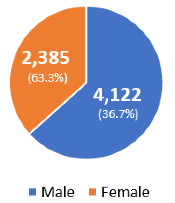

Further calculations have been made possible by the 4th CMS FoI[5] which split the total deaths of paying parents in arrears into Male & Female groups. As a result, we could calculate that:

a) 140 of the deaths of paying parents with arrears were female

b) 5% of paying parents are female based on a CMS report into overcoming risks of non-compliance by paying parents[25] and we assumed that figure is consistent in paying parents with arrears, giving a figure of 2,684 female paying parents with arrears, from which 50 were dying each year.

- The financial effect on paying parents

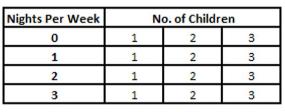

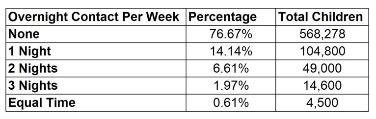

In order to investigate the claims of CMS inflated maintenance calculations and the extent of the potential contribution of the CMS to parent poverty, a profile for 12 paying parent-child contact scenarios (Table 1), ranging from one child with three nights of contact per week, to three children with zero nights of contact per week (Table 2), was constructed based on; national average living expense data, taxation rates at each salary band from a gross income of £10,000 to £150,000, the amount of CMS child maintenance payments at each salary band, and the take home pay per month of each salary band after government taxation. These were used to construct an average paying parent profile which considered the CMS average of 1.5 children per paying parent[26] and the percentages of parents under CMS with zero nights, one night, two nights and three nights of contact per week with their child(ren).

|

Table 1: The 12 scenarios of paying parent’s contact with their child(ren). Contact ranges from 0 to 3 nights per week. Number of children ranges from 1 to 3. |

|

Table 2: Percentages of paying parents with no contact, one night contact, two nights contact, three nights contact and equal time with their child(ren) and the total number of children in each situation. Adapted from Table 5 (J-30 provides total number of children covered by CMS arrangements) Table 6 (cells V-11 to V15 provide total children/nights with NRP) & 7 (cell 0-33provides total number of paying parents)[26] |

The basic living cost varies for each individual, however, in order to investigate the way in which current CMS maintenance costs impact the average individual, an average basic living cost per month required calculation. To enable this, the average cost was calculated to include rent, council tax, and other typically unavoidable regular costs, and were based on the assumptions that:

● The paying parent left the family home after separation (this is common)

● Only a small minority will have bought outright or mortgaged a home upon moving out of the family home and therefore rent privately or are in social housing

● Paying parents are in private rented accommodation as 95% of paying parents are male[27], and males without a greater share of childcare are considered the lowest priority for social housing

● Paying parents own (or have use of) a car without any outstanding finance

● Paying parents have no prior health issues and are therefore not paying for regular prescriptions.

● Paying parents are a non-smoker and not a heavy drinker

- Government increased tax yield

The NRP annual salary required to sustain an adequate standard of living with child maintenance payments, and without child maintenance payments, was calculated based upon average living expenses, taxation rates at each salary band, and child maintenance amounts at each salary band. The income to the government from taxation at these two salaries was calculated using The Salary Calculator[21]. The difference between these shows the increased taxation yield per parent, and multiplying this by the total number of parents under CMS oversight shows the potential total increased tax yield.

- Impact of Covid-19 on CMS enforcement activity and Parent Death

With the 6th FoI[7] rolling data forward to include December 2020, it was possible to calculate what effect the Covid-19 related reduction in CMS enforcement activity had on parent death. Enforcement activity is provided in CMS quarterly reports, all 21 of the CMS enforcement measures were added together and then divided by 21, then 2019 was compared to 2020 data provided in the December 2020 reporting[28].

Results

Proportions of Deaths of Parents in Arrears vs not in Arrears

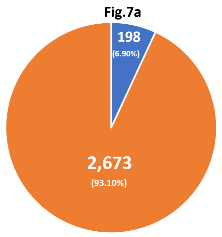

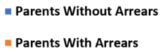

The CMS data provided estimates that of a total of 435,900 paying parents, 53,700 were in arrears, and 382,200 were not in arrears within the 34-month period. This means that the parents in arrears sub-group constitutes 12.3% of all paying parents as of March 2020. The annual deaths per 100k of population for parents with arrears and parents without arrears was calculated according to the total number of deaths stated in the FoI[3] in order to be able to directly compare the mortality rates. This found an annual death rate of 1,880 per 100,000 for the parents in the arrears subgroup, and 141 per 100,000 for the parents not in arrears (fig.3). This means that the deaths within the paying parents in arrears group constitutes 65.15% of the deaths in the paying parent’s population despite having a population size 7.1 times smaller than the parents not in arrears subgroup

|

Figure 3: Table summarising the CMS data for parents with arrears and parents without arrears. This includes the values given by the CMS of total number of parents and total number of deaths within the 34-month period, as well as adjusted numbers to give the annual deaths and annual number of deaths per 100k of population of the two subgroups. |

||||||||||||||||||

The ONS mortality rates of UK age years 30-49 from 2016[29] (their most recent data sets) were obtained; the annual number of deaths per 100k of population per year is summarised in figure 4. These were used to compare to the paying parent mortality rates because the most common age range for paying parents with arrears under CMS care is 30-50.[30]

Figure 4: The ‘all-cause’ mortality rates per 100k of population for aged 30-49[29] |

|||||||||||||||

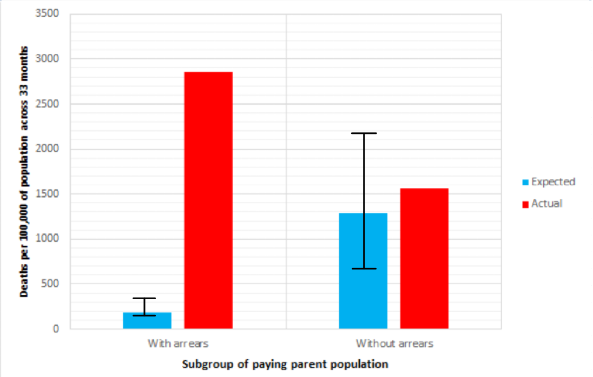

This data was used to calculate the expected number of deaths of the two subgroups, according to their given population size, across the 34 months, so these values could be compared with the actual number of deaths as provided by the CMS. 123 annual deaths per 100k of population per year was calculated to be the average across UK ages 30-50 in 2016. This was used to calculate an average of 187 expected deaths out of the 53,700 parents in arrears, and an average of 1,332 expected deaths out of the 382,200 parents not in arrears within the 34-month period (Fig.5).

Figure 5: Expected number of deaths as predicted by ONS national death rates for the ‘with arrears’ and ‘without arrears’ subgroups over a 34-month period |

||||||||||||

For a more accurate comparison, the potential range of expected deaths was calculated according to the lowest mortality rate (age 30-34) and the highest mortality rate for the general UK population (ages 45-49), as the specific age distribution within the paying parents’ subgroups are not currently known. This gives the margin of error for which these averages fall within. These figures were compared to the actual number of deaths within the subgroups in the 34-month period (Fig.6, Fig.7).

Deaths of parents in arrears exceeded their average expected value of deaths by 2,673 over 34 months, therefore giving this group a mortality rate of 14.28 times (a 1428% increase) the expected rate for its population size. A substantial proportion of parent deaths, therefore, cannot be reasonably explained according to the national average for their age group, as exemplified by Fig.6. The validity for using 30-50 as the average age range for paying parents is strengthened by data found in the publicly available DWP data interrogation tool Stat Xplore[20] which confirms 73% of paying parents are aged 30-49. Figure 6 also demonstrates that even though the exact ages of parents in arrears is unknown, and therefore there may be discrepancies when calculating expected death rates, even if the highest average mortality rate was used to calculate the expected death rate (age 45-49) the actual death rate of these parents would still be substantially higher than the expected death rate for their age. This is shown by the black error bars on Fig.7, which shows minimum and maximum expected death rate according to the ONS data[29]. This considerable difference is highlighted when compared to the difference between the expected and actual death rate for the parents without arrears. Fig.6 shows the actual death rate of parents not in arrears to lie within the error bar range which shows the maximum and minimum possible expected death rate according to the ONS data. This suggests that despite the actual death rate being higher than the average expected death rate for the group, there may not be a significant difference, a discrepancy which requires further information on the specific age splits of the paying parents to qualify.

Figure 6: Table summarising the difference between the actual, and expected number of deaths according to the average ONS mortality rate for age 30-49[29]. | ||||||||||||||||||||

Expected vs actual number of deaths of paying parents by with and without arrears subgroups Figure 7: Comparison of the numbers of expected (blue) and actual (red) death paying parents with arrears and not with arrears per 100k of population across 34 months. The bars shown in black present the minimum deaths we would expect if all paying parents were at the lowest of the age range (30), compared to the maximum we would expect if all paying parents were highest of the age range (50) | ||||||||||||||||||||

The number of excess deaths was calculated using the difference between the average expected number of deaths and the actual number of deaths. This reveals the total number of excess deaths across both subgroups to be 2,871 per 100k of population, with 2,673 of these deaths being parents in arrears. Parents in arrears therefore constitute 93.1% of the excess deaths despite being only 12.3% of the paying parent population. This imbalance is displayed in Figure 8.

|

Fig.8a Fig.8b

Figure 8.a: The relative proportions of excess deaths of paying parents with arrears (blue) and excess deaths of paying parents without arrears (orange) Figure 8.b: The relative proportions of size of population of paying parents with arrears (orange) and paying parents without arrears (blue). |

Focus on Impact to Female Paying Parents

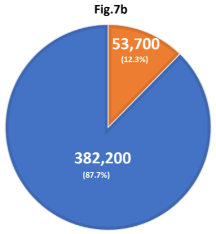

Suicide among females is substantially lower than among males, the national age standardised rate for female suicide was 5.4 per 100,000 of population in 2018[31], compared to 17.4 per 100,000 for male suicides, therefore female suicide represents less than one quarter of total UK suicide.

|

Figure 9: UK Suicide by gender 2018[31] |

If there is any truth to the common view that male suicide is so much higher than female suicide due to the reluctance of males to talk about their feelings or seek help, then we would expect the suicide rates among females to reflect this, i.e. the rate to be ¼ of what we see among male paying parents with arrears. However, what we find is quite different, as shown in figure 10 below.

Figure 10: Table summarising the CMS data for parents with arrears and parents separated into Male & Female subgroups. This includes the values given by the CMS of total number of parents and total number of deaths within the 34-month period, as well as adjusted numbers to give the annual deaths and annual number of deaths per 100k of population of the two subgroups. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Using the same ONS all-cause mortality rate already referred to of 123 per 100,000 of population, we could identify the expected mortality rate for this group by dividing 123 by 2,684 then multiplying by 100,000, which identifies that we should have seen only 3.3 deaths per year (9.36 over the full 34-month period). We could then divide the 50 deaths per year within this group by 3.3 to discover that the death rate for female paying parents with arrears is 15.18 times the ONS rate of 123 per 100,000 of population, giving us a rate of 1,867 per 100,000 of population. The female suicide rate for the UK is 5.4 per 100,000. If all these female excess deaths are suicide, the rate is 50 minus the expected deaths of 3.3 to give 46.7, then divide by 2,684 (which is the number of female paying parents in arrears) and then multiply by 100,000 to give a likely suicide rate of 1,740 per 100,000 of population, which is 322 times the UK female suicide rate.

|

Figure 11: Table summarising the difference between the actual, and expected number of deaths according to the average ONS mortality rate for age 30-49[29] |

||||||||||||||||

From this information it is possible to calculate and compare female paying parent death rates and provisional suicide rates to the national age standardised rate as shown in figure 12 below.

|

Fig.12.a

Fig.12.b

Figure 12.a: The female paying parent death rate and provisional suicide rate compared to UK overall [28] [30] Figure 12.b: The male paying parent death rate and provisional suicide rate compared to UK overall[28] [30] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Comparing these tables demonstrates that the female death and provisional suicide rate is almost identical to male CMS paying parents when separated into groups by sex. Not only does this undermine commonly held views that male suicide is substantially higher than female suicide due to reluctance to talk about feelings and seek help, but in the context of this study, it is a clear identifier that CMS maltreatment has increased the excess death rate (and provisional suicide rate) of female parents in line with male parents, and therefore must be considered to be a causal factor for the excess deaths of paying parents with arrears, regardless of whether or not they are male or female, and there is no sexual discrimination by CMS present when it comes to the maltreatment of NRP’s. Should a greater share of the NRP population become female in the future, without substantial reform of CMS, we can predict that the overall UK female suicide rates would increase exponentially as a direct result, such that were the gender balance reversed, female suicide could be predicted to increase by 49% and the gender share of overall suicide would change as shown in Figure 13.

|

Fig.13.a Fig.13.b

Figure 13.a: The current gender split of annual UK suicide Figure 13.b: The predicted gender split of annual UK suicide if NRP & RP roles were reversed |

The CMS making the claim that the deaths of parents in arrears were attributable to a total population ranging from a low of 241,450 to a high of 317,920, called into question the calculations made above. It was therefore necessary to gather further data which has been provided within the response to the 6th FoI request[7]. The delay and additional work required has however proven to be unexpectedly useful, while also strengthening the reliability of the assumptions that were made to arrive at the results above.

The 6th FoI[7] provided 2 tables of data, both included monthly parent deaths from September 2017 to December 2020, giving us 3 clean calendar years of data to work with. However, Table 1 was deaths of parents with arrears who had an ongoing liability to pay at the time of their death, and Table 2 was deaths of parents whose liability to pay had expired prior to their death.

The table in Fig.14 below has been created using data taken from Stat Xplore[20] shown in the table at Fig.2 on page 10, which distributes the number of parents with ongoing liability who are in one of five arrears bandings (Nil Compliance, Band 1 - up to 30% compliance, Band 2 - 30% to 60% compliance, Band 3 - 60% to 90% compliance and Band 4 - over 90% compliance). This exercise has revealed that even if there is an even spread of parent deaths across all these bands (which would be the best-case scenario for the CMS), the death rate is 3.3 times higher than the expected rate of 123 deaths per 100,000. Conversely however, in the worst-case scenario, where these deaths are concentrated in the Nil Compliance band, the death rate is 10.2 times the expected rate.

|

Figure 14. A Table showing the death rate scenarios based on spread of deceased parents across the compliance bands, separated by years then aggregated to combine all 3 years. |

This final data set also revealed further useful insights which demonstrate the causative link between parent death, ability to pay and enforcement practices (including potential maltreatment) by the CMS. Utilising data found at Table 7.1 of the December 2020 National Tables for CMS reporting[28] where a total of 21 measures for tracking enforcement activity are listed, we were able to calculate the reduction in activity between 2019 and 2020 to be 28.45% and compare this to the reduction in the parental deaths in Table 1 of the 6th FoI[7] between the same years, which at 28.8% is an almost identical reduction to the death rate (despite an increase in paying parent population of 5.47% from end of 2019 to end of 2020), providing the strongest possible correlation to the reduction in enforcement activity (due to Covid-19), and therefore a compelling causative relationship between CMS enforcement activity and excess parent death is established. On a positive note, the reduction in parent deaths as a result of reduced enforcement activity, means that approximately 300 paying parents are still alive who otherwise would not be, albeit that this may be merely a ‘stay of execution’, as the organisation returns to business as usual.

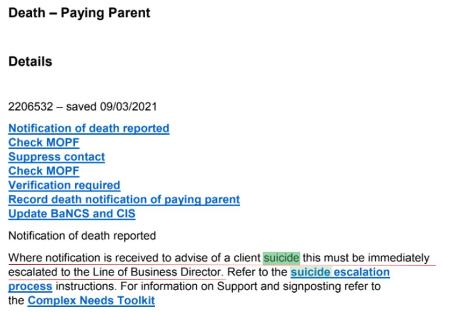

Not only do the above insights demonstrate that the CMS is wrong to determine that there is no causative link between parent death and their practices, but it has also come to light that the CMS are both aware of the problem and are either failing to report it to government, or they are reporting it but government ministers are covering it up and continuing to allow the CMS to carry on causing this large-scale life ending harm. On the 26th April 2021 the CMS responded to an FoI request submitted by M. Peberdy[8], attaching the Death of Paying Parent Procedures for 2016, 17 & 18, each of which contain the instruction shown in Figure 15.

|

Figure 15: An excerpt from CMS internal documentation disclosed under FoI (8) |

The sentence I have underlined in red is key here, “Where notification is received to advise of a client suicide this must be immediately escalated to the Line of Business Director.” This single sentence proves not only that CMS are withholding the truth about their knowledge of paying parent suicide, but they have been keeping a count as a matter of policy. In addition to this, the final response by CMS in the thread of this FoI request, contains some 37 attached documents which extensively detail the procedures CMS staff must follow in the event of a threat of suicide made by a paying parent. These disclosures contradict the multiple requests (14 are listed on the website What Do They Know[32] when using search term “Child Maintenance Suicide”) they have received asking for numbers of parents who have committed suicide, where they state that they hold no records as to the cause of parent death. Not only do these procedures indicate that threats of suicide from desperate paying parents are common place, but also that records are being kept of both the threats and when actual parental suicides are reported to them. It is without question therefore, that the CMS has a count of all suicides reported to them over the course of the years in which these procedures have been in place, and it is therefore essential that this data is made publicly available.

Do CMS have access to adequate technology and skill to identify, analyse and report the problem?

On

3rd February 2021 I submitted an FoI request under reference FOI2021/09402

asking “Please provide a copy of all correspondence between CMS and the minister responsible for CMS where parental mortality for whatever reason and howsoever referred to from the date that the CMS was established (or the earliest available) up to the latest available.”

The request was refused under time and cost exemption. I went back to the CMS to advise them that an administrator of Microsoft Outlook would have a search capability enabling them to carry out a keyword search to identify the required emails very easily, and I sent them a link to the necessary Microsoft documentation[33] and the following list of keywords to search:

● Death

● Mortality

● Suicide

● Died

● Passed Away

● Coroner

The request was refused again on the claimed basis that they do not have access to such a search facility, which seemed extremely unlikely, and so prompted a separate FoI asking which software package is in place to manage CMS emails, there response on 29 June 2021 was "Microsoft Outlook"[34]. I have now pointed out their prior erroneous refusal and requested they carry out the original request[35].

On 22nd April 2021, I was alerted to CMS having engaged the services of Indesser (https://www.indesser.com/), a private business, jointly owned by the government and TDX Group. Indesser were awarded a £500m 5yr government contract in 2014, £15m of which has been spent by CMS. Figure 16 below contains text excerpted from the Indesser website, and it is clear from this that not only do they have extensive data retrieval, interrogation and analytical technology & expertise at their disposal, it is the very core of what they do as a business. However, that capability seems only to be put to work finding new ways the CMS can successfully enforce payment from parents.

|

Figure 16: Excerpt from Indesser website |

The Financial Effect on Paying Parents

The average basic living cost was calculated to be £1,979.85 per month, not including any contributions to a pension, leisure & entertainment, holidays, or caring expenses for their child(ren) if they do have contact. Figure 17 depicts the cost items and the amount per month that were used to create this average. This average was used to calculate how much disposable income NRPs are left with, in each of the 12 scenarios, after deduction of tax, child maintenance, and average base living cost, at each salary band from £10,000 to £150,000.

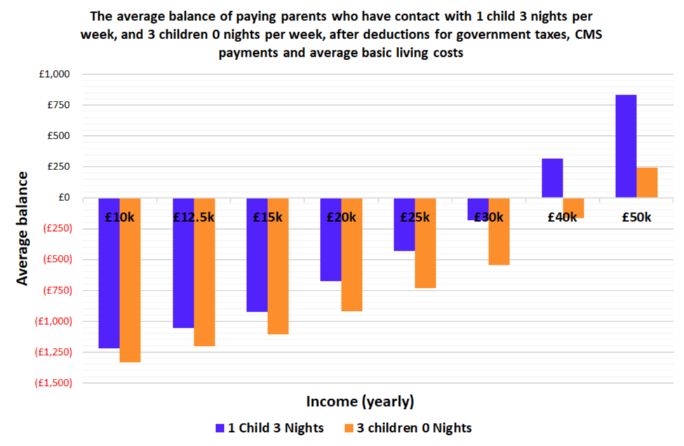

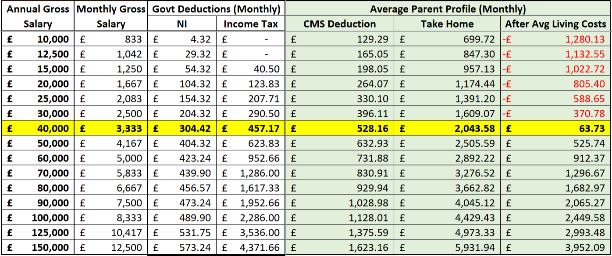

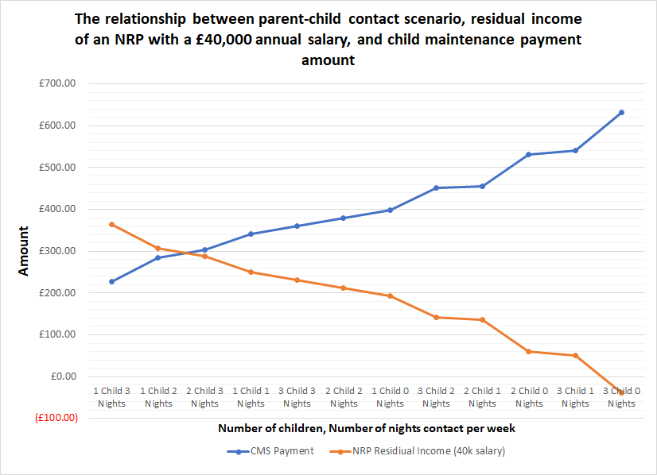

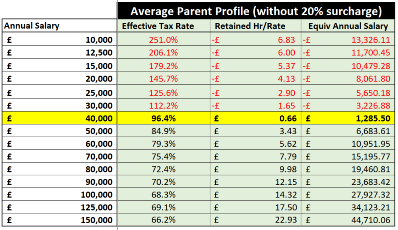

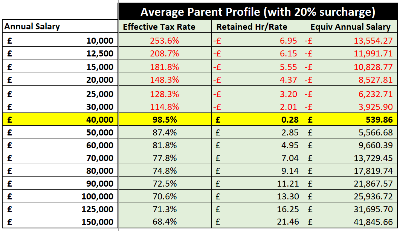

It was found that across all 12 paying parent profiles constructed, in order for the parent to have any residual income after deduction of average basic living costs, taxes and CMS child maintenance payments, they had to be earning upwards of approximately £40,000 per year. At every salary band lower than this, paying parents were in an increasingly severe deficit each month. The extent of the deficit is shown to be directly proportional to the number of children the parent has, and inversely proportional to the number of nights contact per week. This is the same relationship of proportionality as between the child maintenance payment amount, the number of children the parent has and the number of nights contact per week (fig. 22). The residual income for two of the scenarios at opposing ends of the spectrum in regards to least and most child maintenance amount, 1 child 3 nights contact and 3 children 0 nights contact, are depicted in figure 18, whereby it is demonstrated that even in the most financially advantageous scenario possible (1 child 3 nights contact), the NRP would still be in a monthly deficit at any salary band below £40,000 per year. In the most severe scenario investigated (3 children with 0 nights contact), even at a £40,000 salary the NRP will be in a deficit of an estimated -£165.44 per month.

|

Figure 18: The average balance of paying parents who have contact with 1 child 3 nights per week (purple) and paying parents who have contact with 3 children 0 nights per week (orange) |

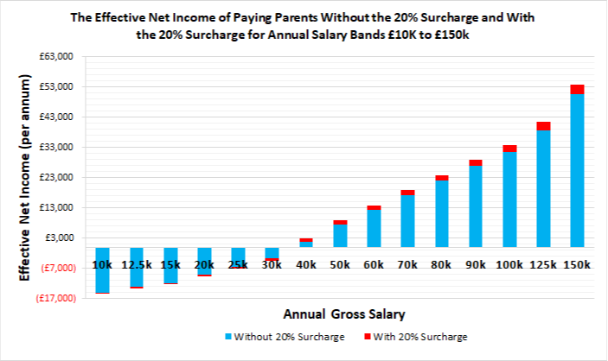

The average paying parent profile, which is based on the average parent under CMS oversight having 1.5 children[26], and was adjusted according to the percentage of parents who have 1, 2, 3 and zero nights contact with their child(ren), demonstrated the same correlation as depicted in Fig.22 and the other 12 profiles for the more specific scenarios. This average profile shows that at a salary of £40,000 per year and a CMS payment of £440.13, the NRP will have a disposable monthly income of an estimated £151.76 (Fig.20). This exampled estimation is only for the situation whereby the NRP is in Direct Pay (i.e. without arrears); should they be moved to Collect & Pay (i.e. with arrears) the additional 20% surcharge to be collected by the CMS further reduces this disposable income to £67.73 (Fig.19). The consequence of this surcharge on the parents’ effective net annual income for each salary band is depicted in Fig.19. This occurs in approximately 34% cases[36].

|

Figure 19: Collect and pay - with arrears

Figure

20: Direct pay - without arrears |

|

Figure 21 |

|

Figure 22 |

● The graph illustrates the financial incentive for RP’s to withhold contact between children and the NRP

● The fewer nights of contact they consent to and the more children they have, the greater the amount of tax-free income they receive

● Conversely, the less time NRP’s have with their children and the more children they have, the more money they will have to pay, the less the income they will be able to retain, the harder they will have to work to generate income, and the more taxation the government therefore will benefit from as a result

How this compares to hourly rates and the National Living Minimum hourly rate

Based on the average 42.5 hours per week/52-week full time working year[37], the effective net income of paying parents only equates to above the National Living Wage hourly rate for 25 and over in 2020 of £8.72[38], when the NRP is earning upwards of £80,000. Salary bands below £40,000 are estimated to be earning negative values per working hour (fig.23). These rates are further reduced for the 34% of parents who are subject to Collect & Pay levies of 20%, as shown in figure 24.[39]

|

Figure 23

Figure 24 |

What does this mean for paying parents?

£40,000 has been the salary highlighted as an example of how these deductions impact paying parents. It has been demonstrated that in all scenarios, the NRP requires a salary of at least £40,000 to be earning the equivalent of above £0.00 retained hourly rate and to not be in a deficit of effective net income. Considering this, as of March 2020, the average income for paying parents is £21,590 and the average income for those on collect and pay is £15,121[40]. This is substantially below even the estimated salary of £40,000 required for the NRP to not be consistently in a deficit every month. According to the average parent profile produced, this would give the average paying parent in Collect & Pay an estimated negative income of -£902.40 per month (fig.24), equivalent to a negative hourly rate of -£5.55 (fig.24).

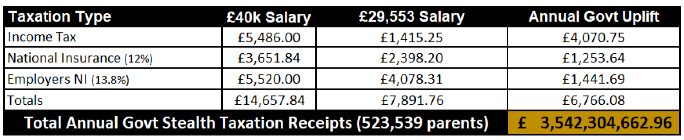

Government increased tax yield

Significant pressure is placed on the NRP to be earning at least a £40,000 annual salary in order to avoid an effective net income deficit each month. This is in comparison to an estimated £29,553 that would otherwise be required to avoid a deficit[21] if CMS payments were not required. For each paying parent able to achieve a £40,000 salary, the total average annual government taxation uplift as a result of the CMS pressure comes to £6,766.08 per parent. This would give an annual taxation uplift to the government of £3,542,304,662.96 (Fig.25) for the 523,539 total paying parents in June 2021. The paying parent total is based on the total number of paying parents according to Stat Xplore[20] in December 2020 (501,966), and the average monthly growth rate since September 2017 (totalling 21,573 additional paying parents). This would represent an increase to taxation by stealth to those affected of 83%[39].

|

Figure 25[39] |

This taxation uplift can be predicted to continue to grow annually with wage inflation, any post coronavirus tax increases, plus the rate of growth of new parents coming into the CMS system. Historic growth in CMS parent numbers between March 2015 and September 2020 is over 80% in 5.5 years.[41]

Predictions

Based on carrying forward historical CMS case numbers growth from March 2015 to December 2020 (as shown in figure 26 below), we can predict that:

● Excess paying parent mortality will more than double from the level identified in this report with double the number of children experiencing the trauma and premature loss of a parent

● The number of paying parents overseen by CMS will increase to almost 1m by July 2028, representing an 1100% increase since March 2015

● The government's annual stealth taxation as a result of the CMS will exceed £7bn

● The CMS will further undermine suicide prevention efforts from all other national agencies and charitable bodies, a doubling of the excess deaths will increase the total male UK suicide numbers by over 20% compared to 2018 level of 4903[31]

|

Figure 26: Predicted growth of paying parent population based on growth rate from March 2015 to December 2020 tracked forward at the same average monthly rate of growth. |

Conclusion

The mortality rate of paying parents who are in arrears with the Child Maintenance Service is approximately 14.28 times the national average. This subgroup forms 12.3% of the paying parent population, however, they contribute 65.15% of the total deaths, and 93.1% of the deaths that are unexplained, within the paying parent population. The fact that the actual number of deaths of parents in arrears greatly exceeds even the maximum possible expected number of deaths for the population size within the 34 months is suggestive of there being a significant difference. The substantial difference between the mortality rate of the two subgroups can only be reasonably attributed to the added financial distress and the harsh treatment by the CMS that parents are exposed to when they are in arrears.

The financial distress of paying parents is suggested to be due to the lack of CMS consideration for the rate of living expense inflation and substantially lower rate of wage inflation since 1998 which results in child maintenance payments not leaving the NRP with enough money to act as a ‘self-support’ reserve to sustain a basic standard of living. This is clearly exemplified as, based on average monthly living expenses, an NRP is having to earn upwards of an estimated £40,000 per year to avoid a deficit each month. This puts the average NRP, who earns £21,590 per annum, in a deficit of a little under the estimated value for a £20,000 annual salary of -£761.39 per month. These figures enable the conclusion that not only are the CMS promoting parent poverty due to their overestimated child maintenance collections, but they are preventing the NRPs escape from poverty as their debt is compounded month on month. This is followed by the CMS 'powerful enforcement practices on those who do not pay, which can be as severe as criminal prosecution leading to custodial sentencing. In order to avoid such severe consequences, NRPs are going into increasingly chronic debt without the earning power to ever reduce this debt. The link between financial distress, debt, lack of hope and suicide is evident. It is therefore a reasonable conclusion that the current CMS practices are a primary causative factor leading to excess parental death as a result of physical and mental illness (e.g. suicide) that are consequences of financial strain and poverty.

The evidently higher mortality rate for parents in arrears, and the evident socio-economic benefits of reducing the deaths in this subgroup, are not only clearly presented, but the data has always been readily available for investigation. This therefore highlights the lack of governmental investigation, an oversight which must, at best, be considered grossly negligent. Due to this evident effect of the CMS on paying parent poverty and the high proportion of deaths within the parents with arrears subgroup, there is no ethical or even legal justification for the CMS to continue to operate this way. The government's increased tax yield from these parents being forced to earn upwards of £40,000 in order to sustain a basic living could be an explanation for continued operation of the CMS in this manner. The benefit of maintaining this pressure on paying parents for the government equates to approximately £6,766.08 annually per parent who is able to achieve the £40,000 salary due to the taxation banding. This potentially identifies the governmental motive for CMS maltreatment of paying parents.

The pressure for CMS to drive revenue was identified in an article published by Voiceofthechild.org in February 2019[42], which references the minutes of numerous CMS management meetings where there is an apparent urgency to drive the percentage split of cases on Collect & Pay vs Direct Pay up to 35% / 65% respectively, in order to plug the funding gap created by a £5.5m budget cut in June 2018. One set of minutes is referenced as stating they are “getting an accelerated growth of switchers from direct pay to collect and pay”, which suggests there is a financially driven desire to move parents across to this method of payment which has been proven to be very rewarding for the CMS.

As this data has demonstrated, a subset of the Collect & Pay group of paying parents (totalling 148,384), estimated to be 53,700 parents experiencing substantial difficulty with CMS arrears are at extremely high risk of suicide, poverty related illness or consequences of homelessness resulting in death. These people require urgent attention to prevent the needless loss of even more parents, and given the scale of this issue, a full and independent Public Inquiry into the Child Maintenance Service policies and practices should be undertaken as well as implementation of a strategy to help the individuals currently in this situation to prevent it from spiralling. This is an indisputable humanitarian crisis that requires urgent attention and emergency intervention.

The calculations of the proportions of excess deaths clearly indicate a strong correlation between being in arrears to the CMS combined with the resulting enforcement activity and substantially increased rates of paying parent death. This is shown as parents in arrears have an average mortality rate 14.28 times higher than expected, with the actual number of deaths being substantially out of the error bars as shown on Fig.7. These results combined with the reduction in paying parent deaths during 2020 compared to 2019, which mirror the Covid-19 reduction in enforcement action, provide compelling proof that the CMS is a major causative factor in paying parent deaths.

As a result of the findings of this paper, which demonstrate the clear causative link between CMS enforcement and excess parent death, it can only be concluded that the CMS must accept the findings and immediately suspend all enforcement activity pending a public inquiry, or alternatively the burden of proving ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ that they have not played a causative role in the deaths of any paying parents must now fall on them.

Discussion

What do the results mean?

The results from the investigation into the financial effects on paying parents suggest that CMS involvement promotes parent financial distress, and that this distress is leading to parent poverty, homelessness and even suicide. This is because CMS maintenance overcalculations leave the NRP without a ‘self-support’ reserve sufficient to sustain a basic and functional standard of living. A compounding effect month on month wherever the maintenance required (and possibly arrears on top) is above the earning power of the NRP, impacted further due to wage inflation since 1998 falling far below ‘cost of living’ inflation.

Our 12 paying parent-contact scenarios suggest that the average paying parent, who is on a £21,590 annual salary, would be in a compounding deficit each month up until they are earning a £40,000 annual salary, when under CMS oversight. That deficit would likely result in an increase to CMS costs further compounding their problem, which would lead to the majority of paying parents effectively earning a negative sum per year largely due to child maintenance payments. This clearly demonstrates how the CMS is implicated in parent poverty.

Previous investigation into the CMS

Prior to this research, the CMS and its predecessor the CSA have historically encountered extensive protesting against their practices due to claims of maintenance miscalculations resulting in inflated arrears as well as the severe enforcement practices which follow, both of which contribute to and promote parent financial strain and poverty. These issues have not only been raised by those personally affected, nor are they limited to related action groups and charities, such as Families Need Fathers and Fathers 4 Justice, but they have been frequently highlighted to the government by various Members of Parliament (MPs). Sir Iain Duncan Smith, MP and former leader of the Conservative party (2003-2005)[43], addressed the issue of current child maintenance practices not only causing parent poverty, but systematically preventing NRPs from overcoming this financial hardship, stating that the NRP has reduced ability to “earn more money to support their children and escape poverty” [15] due to reduced work incentives for the RP. On page 3 of this document, Sir Iain further articulates that the cause of the extreme financial hardship is the lack of a “self-support” amount of money left for the NRP to ensure adequate standard of living when they are paying the RP maintenance.

“This [the ability of paying parents to escape poverty] is compounded by outdated minimum income thresholds for the payment of child maintenance which were set in 1998. Unlike many countries, the UK has no “self-support” reserve factored into calculations; instead, minimum income thresholds for payment are set out in legislation which is now twenty years out of date. There has been no adjustment to take into account inflation over that period. This means paying parents are no longer able to maintain the standard of living they were initially intended (in law) to have and many face financial hardship.”

Here, Sir Iain clearly identifies that the payment thresholds used by the CMS are calculated based on what the UKs economic state was in 1998, therefore not regarding inflation over that period and leaving parents in a financial situation that is insufficient even to provide for their own basic needs in a modern society. Not only are the payments miscalculated in this manner but when a parent is unable to pay, they are further impacted by CMS adding a 20% penalty, substantially worsening their financial situation. This lack of adaption to incorporate the rise of basic living cost due inflation means that the current CMS payment calculations do not leave the NRP with enough money to maintain the intended (by law) standard of living, leaving many many parents in severe financial strain if not poverty.

Long before Sir Iain highlighted this issue to government, the relationship between a parents ability to pay, enforcement upon them and payment compliance, was investigated by Bartfield et al (1994) to identify both inability to pay, and lack of earning power as significant barriers to compliance.[44] Bartfield et al stated that their results suggest that a father’s ‘ability to pay’, is a determining factor in the extent to which he ‘fulfils his child support obligation’, whereby they concluded that increasing the earning power of the NRP would increase child support collections. This conclusion suggests that NRPs are prevented from providing child support, not by their lack of desire to, but by their lack of earning power impeding their financial ability to. This problem was initially addressed by Bartfield et al in 1994, in a modern-day society, cost of living has increased markedly, with wage inflation not keeping pace. Despite this, the child maintenance payments calculations have not adjusted to take this financial reality into account. It can therefore be reasonably concluded that the inability of paying parents to fulfil their child support obligation as a result of inability to pay would be substantially increased since Bartfield et al’s conclusions in 1994, due to inflated cost of living without any adjustments to CMS assessment criteria since 1998.

Whilst this impact of CMS involvement on parent poverty has been addressed, the extent of involvement in unexplained parent death as a result of this CMS influenced poverty has not been investigated. The lack of prior investigation can be considered, as a minimum, grossly negligent due to the substantially and consistently high mortality rate of paying parents in arrears and the frequency over many years that campaigners have brought this to government and CMS attention. This emphasizes the consequential importance of this report as it aims to identify the extent of the correlation between parents in arrears under CMS oversight and high mortality rates, as well as highlight potential causes.

How CMS induced financial stress could be leading to increased mortality of paying parents

Due to the involvement of financial strain in physical & mental illnesses, the deduction that the deaths of parents in arrears is contributed to by the CMS enforced parent financial difficulty, is well reasoned. This association between debt and mental health issues is demonstrated by various studies, such as by Edwards et al (2003)[45] who found that 64% of 374 individuals who were seeking debt advice from a UK consumer advice service reported their debt problems to be a main cause leading to stress, anxiety and depression, with over ¼ of this group seeking GP treatment for these mental health conditions. This association is validated by a large source of supporting findings, such as by Reading and Reynolds (2001)[44] who concluded after a longitudinal study that debt was the strongest socio-economic predictor of depression .Reading & Reynolds (2001). Findings such as these elucidate the way in which being in arrears to the CMS could contribute to the worsening mental health of paying parents. In circumstances where a paying parent is falling into arrears, to then inflate costs by 20% (which is happening in more than ⅓ of cases and growing) could be considered a ‘poverty penalty’ which, in the majority of cases, can only result in a larger level of debt than the parent has any prospect of sustaining or overcoming. This effect of the CMS on paying parent mental health is demonstrably leading to suicide, other mental health related deaths or deaths resulting from the consequences of homelessness, and is therefore a potential explanation for the link between being in arrears and a 14 times increased risk of mortality.

Not only does being in debt increase risk of death due to exacerbating mental health conditions, but being in debt often results in the individual living in poverty, which itself is implicated in worsening physical illness and therefore the deaths associated with physical illness. Extreme debt can lead to homelessness / rough sleeping and the associated elevated risk of death from; exposure to violence, exposure to the elements, exacerbated ill health, malnutrition, lack of access to healthcare, increased likelihood of misuse of alcohol or drugs and the increased likelihood to make poor decisions that may result in a danger to life/health as a result of deprivation induced desperation. An audit in 2017 revealed that “41 percent of homeless people reported a long-term physical health problem and 45 per cent had a diagnosed mental health problem, compared with 28 per cent and 25 per cent, respectively, in the general population”[47]. This data is not directly comparable as it is based only on people who are homeless and who likely have various additional contributing factors to their ill health. As well as this, there is yet to be accessible data identifying how many parents in arrears with the CMS become homeless as a result of their financial difficulty. However, findings such as these act to demonstrate the substantial effect of poverty on physical and mental health issues, both of which increase mortality rate. This therefore elucidates the way in which CMS induced poverty is connected to the alarming paying parent death rate. This effect may be further amplified by the fact that, as previously stated by Sir Iain Duncan Smith, being in arrears with the CMS reduces ability to escape poverty in the future, diminishing the hopes of the paying parent of ever being in a better financial situation, which could understandably worsen mental health problems and potentially contribute to suicidal ideation. This association is further strengthened with the findings of Weich and Lewis (1998)[48], who revealed that “financial strain was a better predictor of future psychiatric morbidity than poverty or unemployment.”

The association between financial strain, debt, poverty, and increased mortality from either physical or mental health causes is repeatedly demonstrated, it is therefore a concern that current CMS maintenance calculations and inflation of arrears are promoting paying parent financial strain, debt, and poverty. This is especially apparent when paired with the considerably higher mortality rate of parents in arrears in comparison with parents who aren't in arrears and the general population.

It is an important consideration that whilst the primary focus of this paper is on the deaths within the paying parent population and the involvement of the CMS, the 2,860 deaths are out of a total of 53,700 parents in arrears who are potentially suffering in a similar physical and/or mental manner prior to a suicidal outcome. This subgroup of the population should be considered a highly vulnerable and at-risk group due to their risk of death being 14.28 times the national average. The mortality of this group is exacerbated not only by financial hardship influenced by CMS involvement but the likely lack of social support (common for recently divorced males), and potentially falling victim to forms of domestic and litigation abuse (further compromising finances and earning power) through family court proceedings.

The Wider Impact of this on Friends, Family Members and the Economy

In her blog on NHS England website in 2018[49], Ruth Sutherland the former CEO of Samaritans said “A suicide is like a rock thrown into the water with the ripples spreading outwards, covering family, friends, soaking work colleagues, acquaintances, the wider community.” Topping the list of factors that Ms Sutherland goes on to explain lead to suicide are relationship breakdown and separation from children. The CMS is therefore positioned at the most vulnerable period of a parent’s life, immediately after separation in most cases, evidently there is a vast majority level of separation from children, and yet no risk assessments have been carried out into throwing into the mix unsustainable financial strain backed up by severe enforcement practices.

Further investigation into the cause of these excess deaths, and intervention based on this in order to prevent them, would be unquestionably beneficial. This would be not only for the parents under CMS oversight themselves, but for their family members (especially their children), friends, colleagues and for the economy. The importance of this, therefore, cannot be overstated. The evidential benefit of preventing the needless loss of up to 1013 lives annually, would also prevent the additional trauma to the family (especially children), friends and colleagues of the deceased. To exemplify the current impact of the mortality rate of paying parents in arrears on their loved ones, consider the average number of children of each parental death to be 1.52[28] to 1.9[50]. This equates to 1,540 to 1,923 children on average per year who suffer the premature loss of a parent, however the authors fear that this figure could be much higher owing to the financial pressure placed on NRP’s amplifying for each additional child they are supporting under CMS conditions. The loss suffered by the children left behind will be on top of other situational difficulties that children whose parents have separated often go through. Although not all of these deaths could be attributed to CMS, where there is any association at all between CMS treatment and parental death by either physical or mental health means, it could be easily prevented, substantially reducing the number of children who suffer premature loss of a parent. When the cause of death is suicide, the impact on loved ones notably increases, with the likelihood of a sibling of the deceased committing suicide multiplying by an estimated 3.19 times[51]. Wilcox et al stated that children who lose a parent to suicide were “three times more likely to die by suicide than children of living parents.” [52] It is estimated that a minimum of 6 people will suffer a “severe impact” as a result of each individual suicide.[53]

This is just an example of how CMS involvement may be impacting not only the parent but the people closest to them. It has to be remembered that the 2,860 deaths in the 34-month period are out of a total of 53,700 parents in arrears who are potentially suffering earlier stage physical or mental ill health that is ultimately leading to such high rates of paying parent death. This means that although there can be a calculated average amount of 1,540 to 1,915 children losing a parent in arrears per year, there are undoubtedly many times more who have to watch those same parents struggle under the weight of severe stress and poverty conditions. As well as this, it is not only the children of the deceased or of the ill who are impacted, anyone who is a parent, sibling, friend, colleague or any other form of close relationship with someone who is suffering mentally or physically will understand how impactful this can be.

Whilst reducing the impact on the struggling parents and their loved ones is a principal drive for the investigation into CMS involvement into excess parent death, there are also larger scale economic benefits that would come from a reduction in this loss of life. The government estimated the total economic cost of each individual suicide across the UK to be £1.67 million (£1,670,000)[54]. This should be compared with the £9.7 million total in arrears that was still owed by all paying parents combined at the time of their death between September 2017 and June 2020 as stated in the CMS FoI response[3]. If only 6 out of the 2,673 (0.2%) parents in arrears were driven to suicide as a result of CMS enforcement practices, the economic cost of their death would equate to more than the total arrears owed to the CMS by all of the paying parents who died in the time period, at £10 million. Given the impact that CMS induced financial strain, poverty, and potentially homelessness has on the mental health of parents in arrears, it is probable that more than 0.2% of these deaths were a result of suicide. 10% of the total excess deaths being suicide would have a total economic cost of £447 million. 100% being suicide would have a total economic cost of £4.47 billion. 62.7% being suicide would equate to an economic cost of £2.8 billon, which is identical to the grand total of all child maintenance overseen by the CMS in the same time period. The urgent requirement to investigate the cause of deaths of the 2,673 parents in arrears is therefore clearly exemplified.

How This is Contributing to Parental Alienation and the Bias Against and Stereotyping of Fathers

The calculation of child maintenance payments by the CMS provides incentive for the RP to further restrict or prevent overnight contact between the NRP and their child/ren to increase their own financial gain and place a harmful financial strain on the NRP. As the child maintenance collection amount increases with the lessening of the number of nights contact the NRP has with their child, the financial gain for the RP is therefore inversely proportional to the NRP-child contact time. The data indicates that this incentive providing the motivation for the RP to reduce overnight contact for the children with their other parent is driving alienation of the other parent as this is a common technique used to achieve this goal. Although this may not be the cause, the high percentage of NRPs that have 0 or 1 nights contact per week with their child/ren (90.81% 1 night or less, 76.67% no overnight contact - see Table 2 on page 12) suggest that the high-level restriction of contact is incentivized by the associated financial gain.

Not only does the data indicated that the CMS practices are promoting parental alienation in this manner, but their involvement in reducing the contact between NRP and child/ren as well as in the NRPs financial difficulty, which affects their ability to look after their child/ren, adds to the common narrative within media of ‘deadbeat dads’[55]. In many cases, the NRP (95% of which are male[28]) is considered a ‘deadbeat’ due to their lack of involvement in the child's life. This lack of parenting time contribution, however, is promoted by the CMS and compounded by the resulting financial strain imposed upon the NRP.

These are crucial areas to consider due to the substantial impact that parental alienation has on the wellbeing of children. Sir Anthony Douglas, former Cafcass CEO, compared parental alienation to ‘child abuse’ or neglect stating that “it can have as devastating an impact as physical abuse and can lead directly to child or adolescent mental health problems.”[56] The acknowledgement of the severity of this impact provides a principal factor which should drive investigation into child maintenance overcalculations, parental financial strain and parental alienation/stereotyping of dads.

Claims of Domestic Abuse by Resident Parents

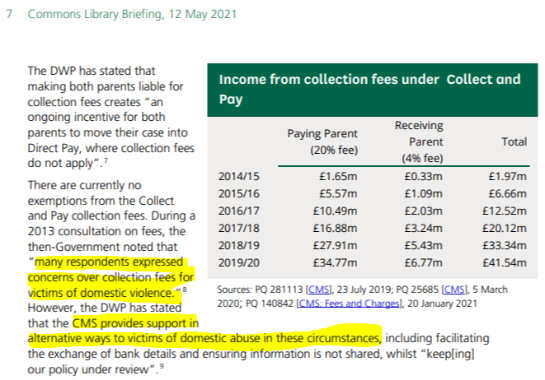

Aside from highlighting the alarming rise in Collect & Pay fee income collected by CMS shown in figure 27 below (increased by a multiple of 21 times between 2014/15 & 2019/20) taken from the CMS Commons Briefing of 7th May 2021[12], the highlighted text draws attention to the concern being shown to how those claiming to be domestically abused are being charged a 4% fee retained from the funds received through Collect & Pay.

|

Figure 27 |

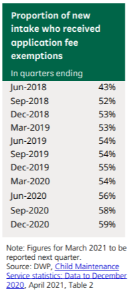

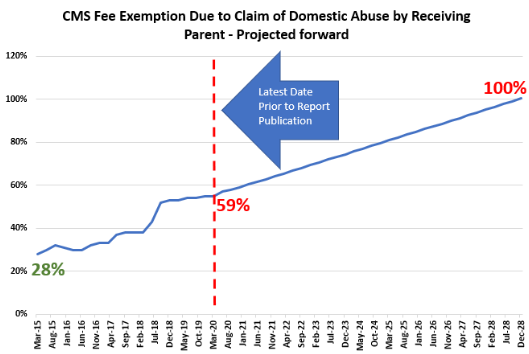

This leads on to the table shown in figure 28 below detailing the prevalence of claims by resident parents that they are a victim of domestic abuse in order to gain exemption from the need to pay the £20 application fee.

|

Figure 28 |